|

|

|

|

| |

MI6 looks at Sir Ken Adam's book in detail with a

double feature examining his work and memories from

Diamonds Are Forever...

|

|

Ken Adam: The Art of Production Design

- Diamonds Are Forever (1)

7th May 2006

Following on from the chapter on Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, Sir

Ken Adam reflects on his work on Connery's last official James Bond

film "Diamonds Are Forever". MI6 brings you an extract from the acclaimed

production designer's book by Sir Christopher Fraying, "Ken Adam

The Art of Production Design".

| Diamonds Are Forever

Then in 1971 you worked on the next Bond film, Diamonds

Are Forever. The big controversy surrounding this film

was that everybody thought it was going to be made in America,

and without Sean Connery.

They even cast an actor called John Gavin, who later became

- I think - the American Ambassador to Mexico for Ronald

Reagan.

John was very good-looking. Yes, he'd appeared in Psycho

and Spartacus.

But eventually a deal was struck with Sean Connery

and the movie shifted back to England. That must have been

quite nerve-racking.

Yes, it was nerve-racking. It was also interesting in a

way because it was my first experience of working in Hollywood,

and because Harry

Saltzman owned Technicolor at the time, which was part

of Universal, we were VIP visitors at Universal Studios.

It was still run like the old classic film studios: the

art department had a pool of over a hundred assistants,

like sketch artists, and the production designer wasn't

allowed to do his own sketches; the illustrators did all

that for him.

They had the most professional staff who were

under contract to Universal and had worked there for years

and years, happy to be either an illustrator or draughtsman.

The chief art director - the equivalent of Cedric Gibbons

- was Alex Golitzen. I found myself in a tiny office without

a window so I said to Alex, `I'm sorry, but I can't work

like this. I need a window.' He said they had twenty art

directors working like this. But we had muscle, so Alex

gave me the only office with a window. The block was called

the Black Tower. In fact, it's still called that. I also

got the best team from the art department to work for me.

Boris Leven, who I was very friendly with, advised me who

to use for the Bond movie. So it worked pretty well. Around

this time Cubby,

who was a friend of Howard Hughes, had the idea of doing

a spoof in a way of the Howard Hughes persona.

|

|

Above: Book cover art

Book Data Stream

Paperback 320 pages

Publisher: Faber and Faber

ISBN: 0571220576

UK

Order

UK

Order

USA

Order

USA

Order

|

Then the disasters struck. The first was whilst Herbert Ross

and Nora Kaye - great friends of ours and I'd done some pictures

with them - were doing a film in Chicago, they lent Letizia and

I their house in Beverly Hills and one morning at six o'clock

we woke up and everything was rattling. Letizia said, `Terremoto,'

which means `Earthquake'. I'd never been in an earthquake before.

Then suddenly everything started going wrong: books fell out of

the shelves, the television fell over, the swimming pool overflowed

like a saucer. And when we got outside, the palm trees were swaying

dangerously. I got a phone call from my sister in London who'd

heard on the BBC that an earthquake in Los Angeles had been measured

at 7.3 on the Richter scale. I was organising breakfast and trying

to get the maid to clear up the mess when the doorbell rang, and

there was Harry and Jackie Saltzman. They had been staying in

the penthouse suite at the Beverly Wiltshire Hotel and she had

grabbed her mink coat and jewels but not much else. Then Guy

Hamilton arrived with his wife Kerima. They were staying in

an apartment on La Cienaga on the twenty-sixth floor and the block

was designed to sway eight or nine feet at that height; can you

imagine?! I don't think Kerima ever fully recovered from the shock.

And lastly there was an Italian screenwriter who arrived clutching

a photograph of his mother! So we became like a refugee camp.

That was the fun of it. And in my stupidity I thought, `Well,

an earthquake is an earthquake. It's over. There are no aftershocks.'

So I drove to the studios - everybody said I was crazy - but there

was nobody there. I got into my office and all my sketches had

been blown all over the place. It was a very modern block; we

used magnetic tape to attach our sketches to the steel walls,

rather than drawing pins. But now the magnets didn't work. I couldn't

get hold of anybody on the telephone. And some of the freeway

had collapsed. So I decided to drive back. It was quite a traumatic

experience, but I can see the funny side of it now. We carried

on planning the film at Universal Studios and also in Las Vegas.

Above: Back cover |

|

For the moon buggy?

Yes, the moon buggy.

And a very important car chase for which Harry had discovered

these French stunt drivers who were able to flip a car on

its side and drive like that. I learnt a lot because Ford

provided all the cars and they had to be properly ballasted

to do this stuff. Basically we all had a very good time,

but I remember Dave Chasman, who was pretty high up in the

UA hierarchy, came to Universal one morning and said, `You're

crazy to do this film with John Gavin.' Dave knew we were

paying Gavin nothing in comparison to the two million dollars

that Sean Connery wanted, if I remember rightly, but he

said we could recoup that money with EADY Money, which was

a tax shelter in England.

In effect, a grant.

So, to cut a long story short, Sean got the film. We were

going to shoot the scenes that we had already set up like

the Las Vegas sequence, the oilrig in Santa Barbara, the

car chase ...

The moon buggy in a gypsum mine close to Las Vegas

...

Yes. Shoot all that there and then film the interiors and

other sets in Pinewood. This was decided late in the day.

For me it was a gigantic logistical problem because I had

nobody from the British Bond team with me. So I rang Peter

Lamont, who was fortunately available to fly out and liaise

with the American art department, and then set up an art

department in Pinewood for when I got back.

|

The moon buggy picked up on the real one we'd recently seen

on television from the moon shot - as ever, reflecting things

that were in the news and extending them.

That was not my idea. Guy Hamilton decided that it should look

grotesque so I extended the mechanical arms. I copied the fibreglass

conical wheels of the real moon buggy but they kept breaking at

high speed on the rough terrain of the moonscape we based on NASA

photographs, so eventually Sony gave me balloon tyres and we completed

the sequence with them. It was nearly a disaster. But Las Vegas

was a fascinating place.

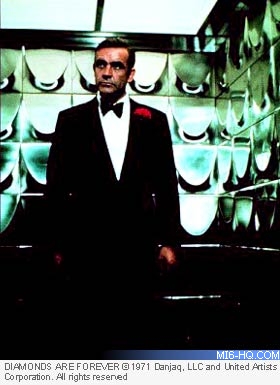

| There's a great shot in the film -

that looks like a futuristic set but I think it's a real

location - of Bond standing in an exterior glass elevator

going up the side of a building. It seems almost science

fiction.

It's partly on location. There was a hotel that no longer

exists, The Sands maybe, and it was a bit like a tower with

one of these exterior glass elevators. I wanted to show

it to a, so I went to the hotel with my 16mm camera and

stepped into the elevator, but a security man told me I

couldn't shoot there.

I told Cubby and he made a call to

Howard Hughes who was living in a penthouse. Hughes apparently

said, `Don't worry about it. Get your production designer

back there and he'll get the VIP treatment.' So I went back

there and everybody was bowing and scraping to me. At the

time, half of Las Vegas belonged to Hughes and the other

half to various syndicates. Cubby even got me permission

to enter Hughes's ranch in Nevada, where the security guards

looked at me and said, `Are you Mr Hughes?' They had no

idea what he looked like!

|

|

|

By this time I think Hughes had a long beard, long unwashed

hair and very long fingernails.

It was amazing. Cubby was the only person who could get through

to him. I was present when he spoke to Hughes on the phone, but

I never met him. So Las Vegas was fascinating. The whole art department

was staying with me at a hotel that belonged to one of those syndicates

and it didn't cost us a cent. But the big problem was that nobody

went to bed. At four in the morning I found my chief draughtsman

- my assistant - in the casino. And there were so many beautiful

women. There were ten women to each man.

Stay tuned to MI6 for the final extract

from Sir Christopher Frayling's book Ken Adam: The Art of Production

Design.

Related Articles

Ken Adam: The Art of Production

Design - Preview

Ken Adam: The Art of Production

Design - Preview

Thunderball

40th Anniversary Pictures Thunderball

40th Anniversary Pictures

Thunderball

40th Anniversary Event Report Thunderball

40th Anniversary Event Report

Dr.

No Production Notes Dr.

No Production Notes

Goldfinger

Production Notes Goldfinger

Production Notes

Thunderball

Production Notes Thunderball

Production Notes

You

Only Live Twice Production Notes You

Only Live Twice Production Notes

Diamonds

Are Forever Production Notes Diamonds

Are Forever Production Notes

Live

And Let Die Production Notes Live

And Let Die Production Notes

The

Spy Who Loved Me Production Notes The

Spy Who Loved Me Production Notes

Moonraker

Production Notes Moonraker

Production Notes

Goldeneye

Rogue Agent Goldeneye

Rogue Agent

Many thanks to Faber & Faber, Sir Christopher

Frayling and Sir Ken Adam.

|

|

|