|

| |

MI6 takes a look at "Talk of the Devil", a collection

of rarely-seen journalism and other writing by Ian

Fleming...

|

|

Talk Of The Devil

21st January 2009

Talk of the Devil is a collection of rarely-seen

journalism and other writing by Ian Fleming. It belongs to a

special

edition of his complete works published in 2008 by Queen Anne

Press to commemorate the centenary

of his birth. The edition

is intended to celebrate Fleming not only as the creator of Bond

but as an accomplished and vivid journalist, distinguished bibliophile

and literary publisher. No uniform edition of Fleming’s

complete works has appeared before. Talk of the Devil, the last

of eighteen volumes, is edited by his niece Kate Grimond and

nephew Fergus Fleming.

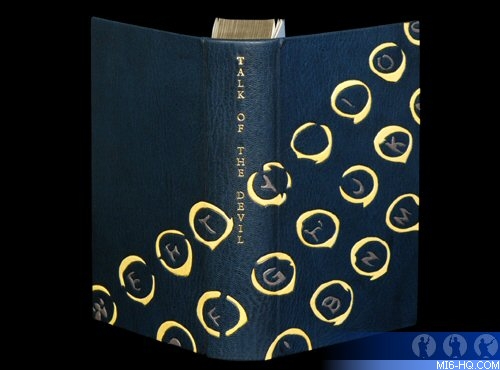

Above: "Talk Of The Devil" Hardcover

|

Preface

“In preparing this volume our goal has not been to assemble

every overlooked scrap of Ian Fleming’s writing, far less

to make a definitive collection of his journalism. Instead we

have tried to create a book that does justice to its author.

The contents have been selected for their rarity, their historical

and biographical value and the glimpses they give of his opinions

and enthusiasms. Our overriding policy has been that they should

be of interest and entertainment.

A few items have never been published,

others have already appeared in print - as, for example, the

articles that Ian Fleming wrote

during his long association

with the Sunday Times. In the latter case we have followed the original typescript

rather than the published version, and where good lines were edited out we

have put them back in. The title is taken from a notebook in

which Fleming listed

names and phrases that caught his fancy. Talk of the Devil, which was an

early contender for Diamonds Are Forever, caught our fancy too.”

At more than 400 pages Talk of the Devil is the longest work

ever to bear Ian Fleming’s name. Its contents are divided

into six sections:

|

Among the unpublished items are two short

stories: A Poor Man Escapes, and The Shameful Dream.

The former is one of Fleming’s earliest

attempts at fiction, written in 1927 at the age of nineteen

while under the tutelage of Ernan Forbes-Dennis and Phyllis

Bottome in Kitzbuhel, Austria. It seems to have been influenced

by the reportage of Berlin-based author and journalist Joseph

Roth.

The latter was written in 1951 but never published for legal

reasons - one character bore too close a resemblance to Fleming’s

employer, Lord Kemsley. The “hero” is a journalist,

possibly based on Fleming himself. Intriguingly, he is called

Bone. A year and a letter-change later Fleming’s new

hero would be Bond.

|

|

|

Other notable entries pre-dating Bond include an eye-witness

account of the 1942 Dieppe Raid; Fleming’s “Memorandum

to Colonel Donovan” which laid down administrative practice

for the Office of Strategic Studies (O.S.S.), predecessor to

the C.I.A.; his contribution as Foreign Editor to the Kemsley

Manual of Journalism; and a lyrical description of Jamaica in

1947.

Taken together the contents but act almost as a glossary to

the Bond novels. Here, in embryo, are Dr. No’s island,

Goldfinger’s smuggling methods, Kerim Bey’s Istanbul,

Mr. Big’s Florida fish-tanks, the armament of Bond, the

octopus of Octopussy and more. There is even an early (if faintly

alarming) version of “shaken not stirred”, written

in 1956 for the American market:

“It is extremely difficult to get a good Martini anywhere

in England...The way to get one in any pub is to walk very calmly

and confidently up to the counter and, speaking very distinctly,

ask the man or girl behind it to put plenty of ice in the shaker

(they nearly all have a shaker), pour in six gins and one dry

vermouth (enunciate ‘dry’ carefully) and shake until

I tell them to stop.

You then point to a suitably large glass and ask them to pour the mixture in.

Your behaviour will create a certain amount of astonishment, not unmixed with

fear, but you will have achieved a very large and fairly good Martini.”

The volume traces Fleming’s delight in gambling, fast

cars, espionage and exotic climes. His fascination with buried

treasure is evident: one article, describing a hunt for pirate

gold in the Seychelles, rates almost as a short story. A rare

foray into politics, the 1959 “If I Were Prime Minister,” shows

him to have been a man of foresight and liberal tendencies who

supported a minimum wage, open immigration and freedom of information,

railed against bad diet, City bonuses and conspicuous expenditure,

and took a surprisingly modern approach to global warming. “The

petrol engine,” he wrote, “is obviously a noxious

and noisy machine and I would gradually abolish it and replace

it by some form of electric motor.” Fleming also pays tribute

to contemporary writers such as Graham Greene, Noel Coward and

Herb Caen, columnist supreme of the San Francisco Chronicle.

What comes across most strongly is his insistence on excitement.

Whether directly or indirectly, he rails against boredom. Title

after title contains the word “adventure.” In “Six

Questions,” 1961, he predicts the following:

|

|

|

“Life will become more comfortable and much duller

and basically uglier, though people will be healthier and

live longer. Boredom with and distaste for this kind of

broiler existence may attract an atomic disaster of one

sort or another, and then some of us will start again in

caves, and life on this planet will become an adventure

again.”

The volume concludes with an Envoi taken

from an interview in February 1964. “One can only be grateful to the talent that came

out of the air, and to one’s capacity for hard, concentrated

effort…. I don’t want yachts, race-horses or

a Rolls Royce. I want my family and my friends and good health

and to have a small treadmill with a temperature of 80 degrees

in the shade and in the sea to come to every year for two

months. And to be able to work there and look at the flowers

and fish, and somehow to give pleasure, whether innocent or

illicit, to people in their millions. Well you can’t

ask for more.”

|

Seven months later, on 12 August 1964, Ian Fleming died of a

heart attack.

Talk of the Devil is his final legacy.

For further information about the Centenary Edition please contact

- [email protected]

Thanks to Fergus Fleming.