|

|

|

|

| |

MI6 trawls the archives to see how critics of

the day received Roger Moore's debut as James

Bond in

the 1973 film "Live And Let Die"... |

|

Time Tunnel: Review Rewind

21st February 2009

New York Times - June 28th,

1973

Torchlight, Voodoo drums. Dark bodies writhe in the mounting

frenzy of some unspeakable tropical rite. Suddenly a door is

flung open and framed within it stands a beautiful white girl

held captive by two monstrous black men. Her filmy white gown

scarcely covering the soft contours of her body, she is dragged — protesting — to

a crude scaffold and there is tied fast.

As if by signal, the ranks of jeering celebrants open

and there advances an executioner, laughing, stomping,

hideously costumed. He holds a poisonous snake in his outstretched

hands, a snake whose bite is destined for the smooth young

bosom.

Whatever the quality of this little scenario, you must

admit that to stick it into a movie these days takes nerve.

Merely to make a new adventure movie in which all the bad

guys are black and almost all the good guys are white,

and which includes in its climax the (near) sacrifice of

a (recent) virgin—takes nerve.

Nerve, and certain insolence toward public pieties, and

a lot of canniness about just what level of sophistication

its audience is up to—all of them qualities that

have characterized the James Bond movies since the beginning,

10 years ago, and that abundantly characterize the latest,

Guy Hamilton's "Live

and Let Die."

There are now eight Bond movies, and though they are the

work of many different talents (Hamilton has directed two

previously: "Goldfinger" and "Diamonds

Are Forever") they do represent a recognizable tradition

in which the whole—or the memory of the whole — seems

to be greater than the sum of the parts. |

|

Above: One of the many special publicity

shots promoting Roger Moore as the new James Bond. "Live

And Let Die"

was the third consecutive 007 movie that had changed the

lead actor. |

The plots tend to flow into each other—one scheme after

another for controlling all the money in the world—changing

their elements to fit changing anxieties (in "Live and Let

Die" the evil is a heroin monopoly operating out of some

Caribbean island kingdom with pipelines into New York City and

New Orleans), but remaining the same in essence.

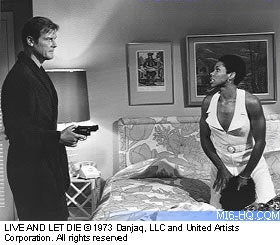

And always there is a woman waiting to be converted by the power

of sex. In "Live and Let Die" she reads the Tarot pack

to tell fortunes for the enemy. James Bond's card keeps coming

up "Lovers," though she thinks she is hoping for "Death."

There are three chases (four, if you stretch a point), including

one by car and motorboat that gets so complicated it allows for

character development. One actor, Clifton

James, who appears

only during the chase, gets fourth billing in the cast list.

|

|

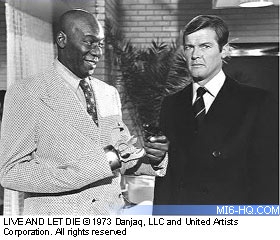

The names above Mr. James's

do not seem so impressive. Roger

Moore is a handsome, suave,

somewhat phlegmatic James

Bond—with a tendency to throw away his throwaway

quips as the minor embarrassments that, alas, they usually

are.

As Solitaire,

to whom the cards speak truth only so long as she remains

a virgin, Jane Seymour is beautiful enough,

but too submissive even for this scale of fantasy. Yaphet

Kotto (Dr. Kananga),

a most agreeable actor, simply does not project evil.

However, I could list compensating virtues by the score.

There is a marvelous escape from an alligator farm (deadly

reptiles are rather a motif in this movie), a superb collection

of grotesque ways of killing, and a fine sense of pace

and rhythm. "Live and Let Die" has been especially

well photographed and edited, and it makes clever and extensive

use of its good title song, by Paul and Linda McCartney. |

Variety - June, 1973

Live and Let Die, the eighth Cubby Broccoli-Harry Saltzman film

based on Ian Fleming's James Bond, introduces Roger Moore as

an okay replacement for Sean Connery.

The script reveals that

plot lines have descended further to the level of the old

Saturday afternoon serial.

Here Bond's assigned to ferret out mysterious goings on

involving Yaphet Kotto, diplomat from a Caribbean island

nation who in disguise also is a bigtime criminal. The

nefarious scheme in his mind: give away tons of free heroin

to create more American dopers and then he and the telephone

company will be the largest monopolies.

Jane Seymour, Kotto's

tarot-reading forecaster, loses her skill after turning

on to Bond-age.

The comic book plot meanders through a series of hardware

production numbers. These include some voodoo ceremonies;

a hilarious airplane-vs-auto pursuit scene; a double-decker

bus escape from motorcycles and police cars; and a climactic

inland waterway powerboat chase.

Killer sharks, poisonous

snakes and man-eating crocodiles also fail to deter Bond

from his mission. |

|

|

Time - July 9th,

1973

There is a new James Bond — Roger Moore of Sainted TV memory — and

a new angle to his latest adventure. In this incarnation, 007

is the Great White Hope. He goes about beating up black men who

are doing a little heroin smuggling to finance a Caribbean dictatorship

and, perhaps, take over the U.S. after they've turned

it into a nation of junkies with their free-sample program.

|

|

Both novelties are deplorable, and Live

and Let Die is the most vulgar addition to a series that

has long since outlived its brief historical moment — if

not, alas, its profitability.

Moore is afflicted with coolness unto death;

one half expects some plot revelation — a saliva

test, perhaps — to explain that the bad guys somehow

got him hooked before the picture started. None is forthcoming, so probably what we have here is

a case of belated fastidiousness: an actor trying to dissociate

himself from a project turning sour all around him.

As for Bond's new character

as a racist pig, there is a dubious rationale for it. Through

the years he has kicked and chopped his way through most

of the other races of man, so it could be argued that it

is just a matter of equal rights to let blacks have their

chance to play masochists to his pseudo-suave sadist. Not

surprisingly, this strained justification fails to relieve

the queasiness Live and Let Die induces.

Why are all the

blacks either stupid brutes or primitives deep into the

occult and voodooism? Why is miscegenation so often used

as a turn-on? Why do such questions even arise in what

is supposed to be pure entertainment? |

In part, the answers lie in the fact that the so-called entertainment

is never really entertaining. A couple of solid citizens, Yaphet

Kotto and Geoffrey Holder, are underemployed as an island dictator

cum pusher and his witchdoctor hireling while Jane Seymour, Gloria

Hendry and Madeline Smith are comely enough but curiously sexless

sex objects. They, like Moore, suffer a sort of weightlessness,

a lack of humanness, which is what Sean Connery as 007 lent previous

Bond adventures. The raunchy adolescent humor that helped audiences

giggle past the ugly inhuman stuff in previous Bond films like

Goldfinger and Diamonds Are Forever is rare and surprisingly

inept. The vehicular chases that have proved commercially successful

in other films are here rendered five times, which is four more

than any movie needs. Setting aside an allright speedboat spectacular

over land and water, the film is both perfunctory and predictable—leaving

the mind free to wander into the question of its overall taste.

Or lack of it.

Related Articles

James Bond Time Tunnel James Bond Time Tunnel

Live

And Let Die - Movie Coverage Live

And Let Die - Movie Coverage

|

|

|