|

|

|

|

| |

During the height of spy mania Time Magazine investigated

the numerous 007-inspired spy flicks...

|

|

Time Tunnel: The Spies Who Came Into The Fold

15th July 2010

TIME Magazine - March 4th, 1966

Movie moguls have long sought the perfect pop-art hero, the infallible

magnetic moneymaker with equal pull for kids under twelve and

adolescents up to and beyond retirement age. Tarzan, a perennial

favourite, still takes to the trees occasionally to fight for

right, but with obsolete weapons. The Wild West gunfighter endures,

though an hombre who traditionally hates kissin' and gets his

kicks by digging spurs into horseflesh seems equally ill-adapted

to the times. The exquisitely contemporary hero is girl-happy, gadget-minded James

Bond, whose legend has already tempted a host of imitators

to bland larceny. Now five new spy

spoofs reverently ape Bond, with more a-making to catch the

rich financial fallout from Goldfinger and Thunderball.

Naked Naiads

The biggest,

noisiest and naughtiest contender in the new spystakes

is The Silencers, with Crooner Dean Martin playing Matt

Helm, a secret agent for ICE (Intelligence Counter Espionage).

Its plot pits Helm against the mastermind of one of those

atomic conspiracies, headquartered in what appears to be

a sunken carrier under the desert near Alamogordo.

But

the real contest is between nudity and gadgetry. The

striptease fun, with Cyd Charisse as team captain, begins

during the

opening credits, then gets right down to business in

Martin's circular bed, which turns, travels, tilts, finally

plunges

him naked into a swimming pool with a naiad identified

as Lovey Kravezit. While the camera plays anatomical

peekaboo, they are dried on two cylindrical Freudian symbols,

then

dressed and breakfasted by machine.

Innuendo roars through Silencers, with nothing omitted save scrawling feelthy pictures on the screen. Now and then, Martin sleepily warbles a song parody, his way of adding sauce to all the gleeful violence, drunken driving and self-conscious smut. Chief compensation over the Ion? haul is Stella Stevens' zany, refreshing performance as a tourist who flees a conducted bus tour and plunges into escapades with the resolute air of a girl making every minute of her vacation count. |

|

Above: Dean Martin as the smooth-talking Matt Helm.

|

Keeping Clean

Intelligence men's intrigues wash

cleaner in To Trap a Spy and The Spy with My Face. Originally

designed for home use, these television retreads are expanded

versions of two episodes from MGM's The Man from U.N.C.L.E. series

(the seams still show). In Face, Napoleon Solo (Robert Vaughn)

seduces Thrush Agent Senta Berger somewhat more explicitly than

he could before, when he had to take time out for commercials.

In Trap, Luciana Paluzzi adds

sex appeal until gunfire spoils her game, but the story really

concerns an ordinary housewife (Patricia Crowley) who helps Solo

foil an assassination plot. A kind of Ellery Queen for a Day,

she goes home with an armful of presents, having scored a clear

win for small-screen morality.

Above: American Robert Vaughn is Napoleon Solo, agent of U.N.C.L.E. and a character that Ian Fleming himself helped to create.

|

|

The man least likely to threaten Bond's supremacy is That Man in Istanbul, with Horst Bucholz battling a one-armed villain atop a minaret and performing other improbable feats to rescue a kidnaped scientist. A masquerade in a Turkish bath, long visits with FBI Sexpot Sylva Koscina and a tour of the city cannot save Istanbul. Delivering insouciant asides to the audience brings out the unseasoned ham in Horst.

Another elusive scientist is the excuse given for The 2nd Best Secret Agent in the Whole Wide World, the most flagrantly imitative spoof of the lot. Its second-best agent is played with studied respect by one Tom Adams, who vaguely resembles Sean Connery. The film sputters with genuine excitement in the scramble for Regrav, a secret process for reversing the law of gravity. But the laws of levity begin to go topsyturvy as well in Agent's craven acts of homage to its prototype. Curling under Adams' sheets, one pussycat purrs: "I met someone like you in Florida. Called himself James . . . James Something." If the bogus Bonds abhor originality, they should at least show enough professional savvy to cover their tracks. |

Mechanical Sin

The least that this spate of spies signifies,

it would seem, is that ventures into venery, sadism and furious action have

set an eyebrow-raising new standard for family entertainment. Kids adore the

lethal, shiny toy collection. Dads happily ogle a prepotent heman, king of

a computerized wonderland in which every foe can be swiftly vanquished, every

voluptuous siren bedded. And women seem quite susceptible to the fantasy of

being vicariously mauled by a master of the art, perhaps after flooring him

with a karate wrist chop. Slapdash, comic-strip plots, more violent than suspenseful,

are made into a joke that viewers are invited to share while soaking up the

sin and splendor of strange locales, gawking at new feats of technology. The

sin is mechanical - a series of clashes between the hostile male and deadly

female, cold sensuality suggesting some futuristic brand of electric sex.

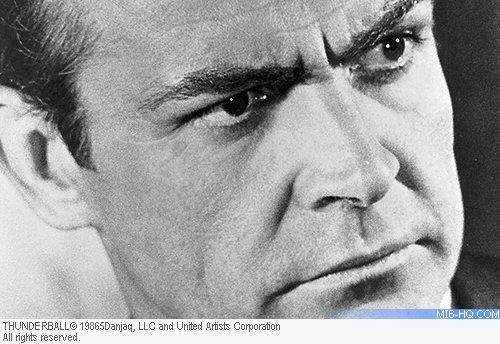

Above: Sean Connery in "Thunderball" which hit the cinemas in 1965.

|

The bizarre, decadent world of the superspy naturally inspires a certain amount of earnest speculation. The Vatican newspaper, L'Osservatore Romano, denounces Bondomania as "a dangerous mixture of violence, vulgarity, sadism and sex," though permissive Dr. Joseph Fletcher, author of Situation Ethics (TIME, Jan. 21), sees it as "healthy fantasizing and myth-making." Dr. Harold Lief of Tulane's Department of Psychiatry thinks Bond's Playboy philosophy may reflect society's changing values and the shape of things to come—"another manifestation of the trend toward greater female aggressiveness, the separation of love and sex."

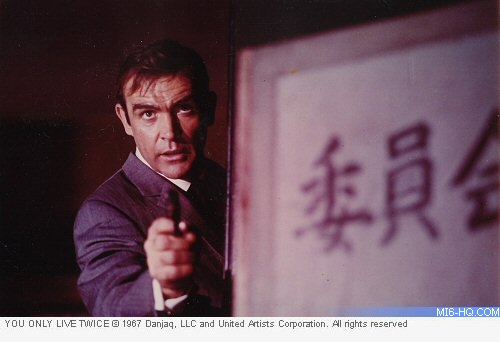

Above: The Scotsman in what he believed would be his final James Bond outing - "You Only Live Twice".

|

Though the surreal James Bond would probably stand up and jeer at such criticism, he might agree with pundits who reason that, in an anxiety-ridden age, it is more fun to laugh at Spectre, Thrush, and ZOWIE than to ponder the threats posed by Mao Tse-tung. The Bondsmen seem far too giddy a crew to inflict any permanent injury on young or old, male or female. As art, the spy spoofs have little value, and they lack even true satirical purpose, or what Critic G. K. Chesterton in A Defence of Nonsense called "a kind of exuberant capering round a discovered truth." A craze occurs when an acquired taste unaccountably becomes an addiction. Without ever believing in it, audiences find the spoofery easy to swallow. But mock espionage may be hard put to survive a throng of second-string undercover men who seem badly in need of vocational guidance.

|

|

|