|

| |

MI6 caught up with Academy Award winner Norman Wanstall

to talk about how working on Never Say Never Again

compared to the official film series...

|

|

Norman Wanstall Interview (2)

20th February 2008

You've worked on the official Bond series but also on McClory's "Never

Say Never Again" - can you describe the differences,

if any,

in the filmmaking approach to these two rival Bond companies?

I accepted the invitation to return to the film industry for Never

Say Never Again because I thought it would be a new adventure for

me and also my experience of Thunderball would be useful to the

production. As it turned out it was a disastrous decision and a

very unhappy experience, and from what I remember it was a pretty

unhappy experience for a lot of people.

Apart from the fact that

instead of the close-knit crew I’d worked with in

the past I was working with people who’d never been

on a Bond film before, we had two guys arrive from the

States who appeared to have a lot of power and from then

on the film seemed to be in the hands of a committee. One

of the guys who was there to keep his eyes on finances

turned out to be a very nasty piece of work indeed, and

caused a lot of bad feeling amongst the crew.

A huge problem for me was

the fact that the production manager (who was always the

one I turned to for arranging my outside recording requirements)

was pushed off the picture soon after shooting, so I was

left to cope alone and spend hours on the phone doing work

that would never normally be my responsibility. Also I’d

always been used to working at Pinewood Studios where the

chief sound mixer Gordon McCullum and I had built up a

good rapport. He loved working on the Bonds and would always

find time for me in his theatre to create difficult sounds

at a very early stage, which made life easier for all concerned

when dubbing began in earnest. |

|

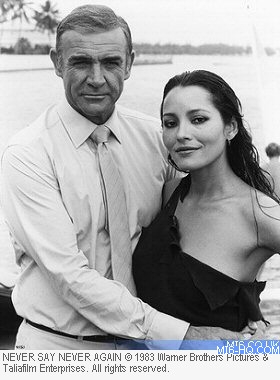

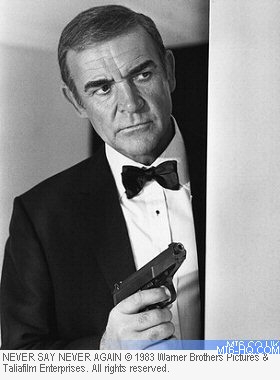

Above:

Sean Connery and Barbara Carrera in Never Say Never Again

(1983) Above:

Sean Connery and Barbara Carrera in Never Say Never Again

(1983) |

Unfortunately Never Say Never Again was made at EMI Elstree,

where the chief mixer Bill Rowe was never available for me to

use his theatre and he’d never even seen a Bond film. As

a result we never developed a good working relationship and I

got no pleasure from the job at all.

The biggest problem by far though was the fact

that the script hadn’t been thoroughly scrutinised before

shooting began, which was unforgivable. The most important rule

in film-making

is that the script must be water-tight before shooting begins,

otherwise serious problems will arise later if there are gaps

in the story-line. In the final version of Never Say Never it

was never explained why Bond decided to go the Bahamas, and it

was never explained how the marines knew where to find Bond when

he was trapped in the cave at the end. There were other areas

in the film where I cringed as lines of dialogue were laid off

screen or on the back of heads in an attempt to explain the lot

plot.

|

|

Finally, when we eventually reached the

dubbing session when all the sound-tracks were mixed together,

we

had a committee in the recording theatre which was a complete

nightmare. Everyone had an opinion on everything, and endless

discussions would arise at every stage. The music did nothing

to enhance the picture and by the end of the production

I was totally disillusioned and couldn’t wait to get

back to my country retreat.

The only positive aspect of the

film was the fact that technology had moved on since the

days of Thunderball and I was put in touch with a man who

could create sounds to order. He had the machines and the

expertise and was invaluable when it came to creating sounds

for scenes such as the electronic table game played out

between Bond and the villain. We projected the scenes in

his studio

and once I’d explained what I wanted he would create

the sounds there and then. It saved me so much time because

in the old days I would have spent hours searching for different ‘ingredients’ and

mixing them together. |

Thunderball by contrast was a very happy picture

and was made very professionally like the previous three Bonds.

McCullum and

I spent a lot of time creating under-water atmospheres and John

Barry took notice of what we were doing so that my tracks wouldn’t

clash with his score. Unlike the previous Bonds though we did

have a few problems with the story-line, and I remember we had

a lot of discussions during the editing process to decide in

which order the scenes should be placed leading up to Bond going

to the Bahamas.

Your last film

credit was "Never Say Never Again" in 1983 -

have you retired from the film industry for good?

I actually retired from the film business around 1977, when

I left the South of England and moved to a new life in the Herefordshire

countryside. I re-trained as a plumbing and heating engineer

and never intended to work on movies again. As it turned out

I did go back to work on Never Say Never and I did occasionally

help out a friend of mine who worked at Yorkshire television.

I remember helping him on a production called Romance On The

Orient Express on which I had to do post-synchcronizing work

with actress Cheryl Ladd and also Ruby Wax. Cheryl was very professional

and a great lady to work with, whereas Ruby was obviously un-familiar

with post production work and it was all a bit of an uphill struggle.

Anyway I soon started to concentrate on my new career and to

all intents and purposes I left the industry for good.

What are your thoughts on the last James

Bond picture, "Casino

Royale", particularly in relation to the sound and music?

I thoroughly enjoyed Casino Royale and I give full credit to

all who worked on it. I thought a couple of the action sequences

went on too long and I wasn’t too keen on the credit sequence,

but apart from that I couldn’t fault it. To be honest I

just sat back and enjoyed it. The Bond movies have changed so

much since the early days and new technology has allowed them

to become more ambitious. Some of the special effects in Casino

were amazing and I couldn’t fault the sound and music.

It was also interesting to see a totally new approach to the

Bond character which was probably overdue. It’s always

a gamble to give the part to a new actor, but Daniel Craig was

superb.

Above: Jan Williams, Norman Wanstall

and Eunice Gayson

at a recent Bond Stars event at Pinewood Studios

|

In your Bond work, what were the most interesting challenges

to experiment with sound effects?

Without doubt the early Bonds were challenging because the

stories were moving into futuristic territory at times and the

sound

technology available still had to catch up with them. I was faced

with the task of creating totally original sounds, such as Dr

No’s nuclear machine, the electronic lift and doors, Oddjob’s

hat, the laser beam, a silenced pistol, underwater atmospheres,

Goldfinger’s moving control desk and the rocket in the

volcano. A lot of the time I didn’t really have the tools

for the job so I had to scout around for ideas. I think it’s

true to say that we were breaking new ground and the Americans

obviously realised that.

Related Articles

Norman

Wanstall Interview (3)

Norman

Wanstall Interview (3)

Norman

Wanstall Interview (1)

Norman

Wanstall Interview (1)

Bond

Music Articles

Bond

Music Articles

Many thanks to Norman Wanstall. Select pictures

courtesy Norman Wanstall.